One’s brain often performs many “automatic” processes without one realising it. For example, one breathes without needing to remind oneself to do so each time. Another similar function that one’s brain does is maintaining one’s balance. It is a finely tuned system that works quietly in the background. Perhaps it’s only when this system goes wrong that one appreciates it!

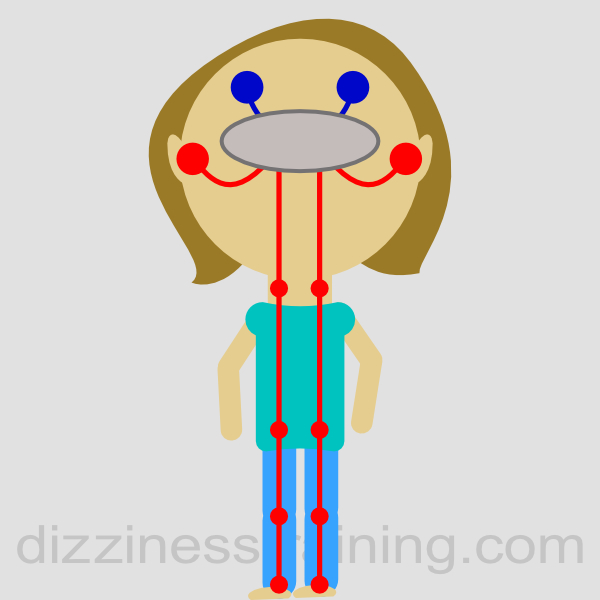

To maintain balance, one’s brain needs continuous “information” about the position of one’s body and it gets this from a variety of sources. Three main sources of balance information are from the balance organs in one’s ears (vestibular organs), position sensors in various parts of one’s body (e.g. neck) and one’s eyes.

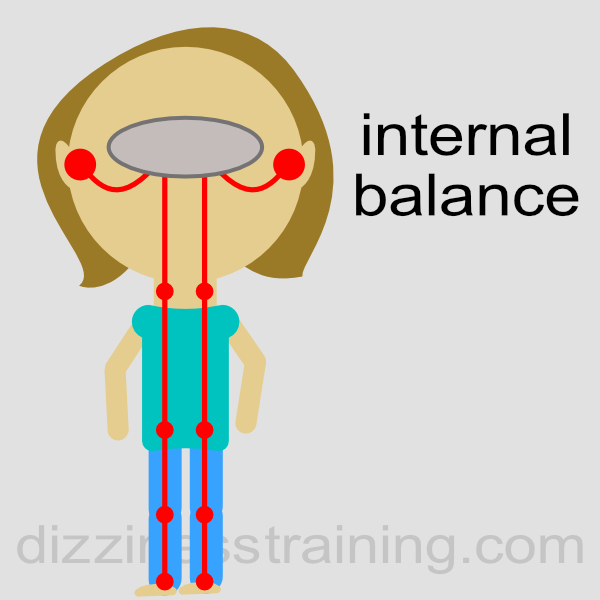

For simplicity, I like to combine the ear balance organs (vestibular organs) and the position information from various parts of the body and call it the “internal balance system”.

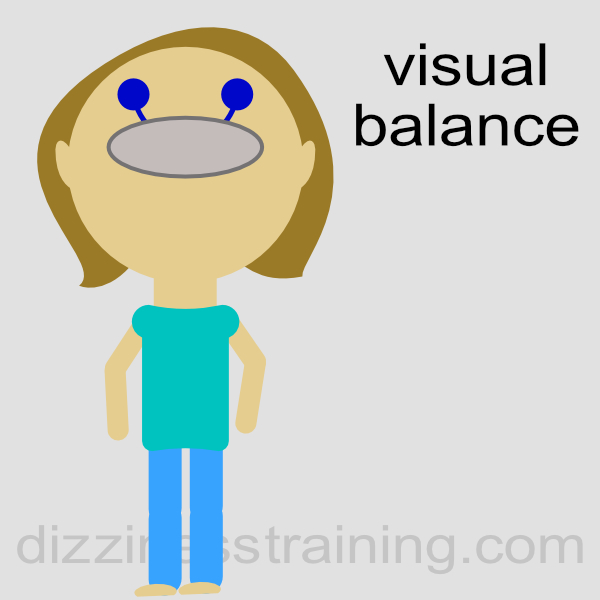

The information from one’s eyes that helps with balance, I call the “visual balance system”. The visual balance system uses visual information from your eyes to adjust balance.

If you are out of balance, your eyes will see a tilted view, and your brain uses this information to get you back in balance. You may not even notice the slight changes in view that your eyes notice, it is a very subtle process.

Normally your brain uses the internal balance system and the visual balance system together in perfect harmony and you keep your balance perfectly without even realising it.

Now let me explain to you my understanding of what happens in PPPD. To start with, PPPD is called a “functional” disorder. This means that there is nothing physically wrong, but rather something wrong with “how” the system is working. One can perhaps understand this using a smartphone as an analogy. A smartphone is a physical object and as we all know, if you drop it, it may crack and stop working. However, a smartphone can also stop working without being physically affected. A smartphone has software or apps which tell the phone “how to work”. If the software gets corrupted then the phone may stop working properly. In this situation, the phone is not physically broken, but rather its software is malfunctioning. Often, all that one needs to do to get the smartphone working again is to reset the software. Now taking this example to PPPD, the symptoms of it are due to “how” one’s brain works rather than there being physical abnormalities in it, i.e. it is a software issue, rather than something that is physically broken. In some sense, this is good news, as there is hope with PPPD that one can reset one’s brain and make it work normally again.

So with PPPD, in what way does one’s brain not work properly? Normally one’s brain uses information from the internal balance system and the visual balance system in perfect harmony. In this situation, one’s brain finds that both systems are telling it the same thing. For example, if you are slightly tilted towards the right, both, the internal balance system and the visual system agree, and one’s brain easily then corrects this balance by sending appropriate messages to the muscles in one’s body.

However, in some people, this happy state of affairs can be upset by what I call, a “trigger”. What I mean by a trigger is something that “upsets” how one’s brain deals with balance information from the internal balance system and/or the visual balance system. To understand how something can trigger the start of PPPD, let us imagine that one develops a physical disease in one of one’s ear balance organs (e.g. vestibular neuritis, BPPV). This could send misleading information to one’s brain. For example, if one is slightly tilted to the right, it may send a false message that one is tilted to the left. This confuses the brain, as now the messages from the internal balance system do not match the information provided by the visual balance system.

Despite this confusing information, one’s brain does not give up. Instead, it tries its best to still keep balance by doing certain things. For example, to reduce confusion it would ignore information from the diseased ear organ and give much more importance to the information provided by the visual balance system. This is not a normal way of working, but it is one’s brain trying its best. This abnormal way of dealing with balance information may cause dizziness. Other things one brain may do in this situation of poor balance information is to stand/ walk in a way that makes one more stable, for example standing with legs more widely apart than normal. The brain also can make one have exaggerated sensitivity to a sense of imbalance, over-correcting imbalance.

At this point in this story, all this makes sense. After all, in the face of one balance organ being diseased and not working, one’s brain is trying its best to cope, even though this may be with the price of side effects such as dizziness etc. The issue, however, is what happens when the disease goes away and the balance organ returns to normal. You would expect one’s brain to become overjoyed and return to the way things were, making one’s dizziness and other issues go away. Unfortunately, in some people, this is not the case and despite now getting correct information from the balance organ, the brain continues to ignore the information. The brain, (and the person who it belongs to!) unnecessarily suffers, making symptoms like dizziness continue. It’s sort of like, say a person injures his or her ankle and walks with a limp. But then imagine, once the ankle is fully healed, the person continues to walk with a limp. PPPD is similar, there is an initial trigger to the balance system, but even though that trigger has gone away, the brain still behaves as if it is still there. This, in essence, is my understanding of what happens in PPPD.

One may ask the obvious question, why does one’s brain do this? I do not know and from what I understand, no one really knows. The human brain is immensely complex and while there are advances in brain science, I think there is still a long way to go to understand in detail why one’s brain behaves in certain ways.

Apart from a disease of balance organs (vestibular events), there are other “triggers” that could start PPPD such as panic attacks, head injuries etc.

Whatever the trigger, the brain in PPPD is quite overloaded when trying to maintain balance. It does not correctly engage with the internal and visual balance system and struggles to manage. This struggle presents to you as continuing (i.e. persistent) dizziness. As one’s brain is already stressed managing balance, anything that “adds” to this stress makes things worse. For example, one’s posture (e.g. standing posture) can stress the internal balance system, and make dizziness worse. Similarly, movement or busy visual places (e.g.supermarkets) can stress the visual balance system and make dizziness worse.

Apart from the brain not correctly using information from the internal balance system and the visual balance system, one’s mind also has a big impact on PPPD. When one feels dizzy and has a sense of falling, one’s mind tries to intervene in what is a normally automatic process. This can lead to anxiety and hypervigilance. One notices even slight imperfections in one’s balance causing anxiety and over-correction of one’s balance. One may also unnecessarily hold onto supports and avoid going to places that make balance worse. This can create a vicious cycle of increasing anxiety and hypervigilance.